|

Araki Hirohiko

Born: June 7th, 1960 in Sendai, Miyagi prefecture

Debut: 1980. Buso Poker (Armed Poker) receives Tezuka Award

Representative works: JoJo's Bizarre Adventure Part 1-8

|

|

Umezu Kazuo

Born: August 3rd, 1936 in Koya, Wakayama prefecture

Debut: 1955. Mori no Kyodai (Siblings in the Woods)

Representative works: The Drifting Classroom, Makoto-Chan, Fourteen |

If you told me that Araki Hirohiko and Umezu Kazuo were starseeds born from the same alien intelligence, or even dimension-shifted doppelgangers of each other, I wouldn’t bat an eye. If anything, this would explain away their eerie similarities—claustrophobic layouts, juxtaposition of gore with guffaws, uncanny youthfulness—while passing as a plot from either author’s archives.

Araki, born by the ocean; Umezu, raised in the mountains. These two opposite forces are drawn together by their overlapping traits, like the eyes of the ying-yang, fated to never meet—until now. TSB has connected the dots to raise awareness of two seminal manga-ka criminally underrepresented in the West. Prepare for thrills, chills, and a degree of plagiarism rarely seen outside of Comiket.

Balance of Horror and Comedy

|

| Makoto-Chan and his pre-school gang. |

Araki follows the same buildup-to-release paradigm to a greatly different effect. He corrals his characters into seemingly inescapable, life-threatening situations of such cruelty and perplexity that they make Jigsaw's death traps look like mere mouse traps. After several chapters of being pushed to their physical and mental breaking point, the heroes eventually persevere and recover with a red-hot zinger fired right between the enemy's eyes. Now it the villain's turn to feel fear.

With Trembling Hands

With Trembling Hands

Araki insists that he writes suspense, not horror, but the end result is the same. He breaks the Shonen manga law governing the economic use of panel space. Above, he exhausts an entire page in a slow reveal, the camera pushing in tighter and tighter like a hand crushing your chest.

|

| Chicken George from Fourteen pontificates on the fall of man. |

This suspense-building technique is hardly limited to Araki—Umezu was doing it years before. And while Araki may have bitten Umezu’s style too hard in the beginning with the Gothic horror and spewing entrails, he later struck out on his own with sunburst panel layouts and unsettling asymmetrical framing. Umezu went in the exact opposite direction, de-evolving into brutal simplicity that bashes the reader’s skull with a rock, again, and again. Violent. And effective.

From costume designs to panel composition, Araki’s current style is unrecognizable compared to his sophomore efforts. JoJo’s cast becomes increasingly androgynous, starting with Fist of the North Star and Rambo inspired roid-heads that deflated into buff hooligans by Part 3. In Part 5 they started sneaking around their sister's closet, and the newest batch from JoJolion dress like they wandered off a Pierre & Gilles photo shoot and onto the soundstage of a Hitchcock film. Araki’s sets have become less cluttered following his jump from a weekly to a monthly format, with negative space filling in the empty pools of black ink that once soaked the page.

Late-term Umezu used enough ink to stain the margins black, but he didn’t start that way. His early work also rode the bandwagon, following the then-popular Tezuka-cartoony style with Mori No Kyodai until shifting with his contemporaries over to Gekiga in search of something more raw. He hit his peak in 1969 with Orochi, vignettes of a supernatural agent whose carefully cropped bangs and silky chestnut locks flowed through pages of immaculate line work, restrained though detailed backgrounds, and macabre beauty.

|

| Painful to draw, painful to read. |

As his stories grew darker in tone, so did the pages, choked in black ink and sharp crosshatching that cut into the readers eyes like garotte wire. By the end of Fourteen, his magnum opus, the nerves in his wrist cinched by the cramped and intense process, his hand struggled to draw even a straight line, his characters, squiggles.

Between Stands named after bands and flagrant plagiarism of fashion illustrators from Antonio Lopez to Tony Viramontes, Araki wears his influences on his sleeve the same way his character Kishibe Rohan proudly sports a Gucchi wristwatch. But Araki's been uncharacteristically reticent when the topic of his inspiration shifts to the grandfather of gore, Umezu Kazuo.

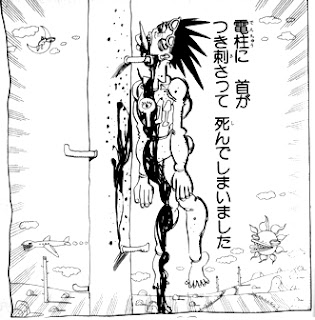

Anyone familiar with the material can attest that Stardust Crusaders borrows its greatest kills from the 1986 splatter title God’s Left Hand, Devil’s Right Hand. The Tower, a stag beetle Stand that nests in the tongue of its user, is one class removed from the the Queen Spider that hides in its master’s mouth, biding its time. Or the megaphone that bursts from a dog to taunt Jotaro’s crew might as well have burrowed out of the Umezu heroine laid out above, right after the tricycle, rusty scissors, and human eyeball.

|

| Probably what Star Platinum has nightmares about. |

The Stands themselves are eerily similar to Umezu's Kage Mouja, a ravenous shade invisible to the naked eye that mutilates all threats facing its host. For further damning evidence, Stands were originally referred to as “ripple ghosts.” Araki claims that he was inspired by the titular guardian spirit from Tsunoda Jiro’s occult classic, Ushiro no Hyakutaro, which was released in the early 70’s, right before another major influence, the desert archaeology adventure tale Babel II. These may have been his formative years, but surely not his definitive ones.

I’m not trying to belittle Araki here—God’s Left Hand, Devil’s Right Hand is a sticky-fingered sneak in its own right, a pastiche of Umezu’s favorite Italian giallo flicks—not that he’d ever own up to creative borrowing, much less even having seen the films in question!

Iron-Clad Internal Logic

A super power that loops time, or a Klein bottle that pours into pocket dimensions—both authors lead you into new disorienting realities that depressurize your sense of disbelief on the way in. But these environments are self-contained in their flawless internal logic. Though you may stumble at first, you’ll be up and running again once your inner ear gets used to the change in atmosphere.

Regardless of how powerful a Stand is, it has limits—range, specific abilities, its physical host. Like a good mystery novel, Araki establishes clear-cut rules and never betrays the reader by breaking them—though the heroes may bend them in a flash of inspiration that saves the day. JoJo doesn’t suffer from enemy inflation, but from rule inflation. By the final showdown, you need a Stanford lawyer to referee the match.

JoJo is grounded in a single world with laws as reliable as gravity, consistent even when stretched across alternate dimensions. On the other hand, Umezu transverses different worlds set in the same universe. Like Ray Bradbury, his works, disguised as Sci-Fi, read as disconnected parables while feeding into a larger truth apparent in his long-form stories. The Drifting Classroom is a toddler’s first step in a journey that terminates in the loss of humanity’s innocence.

On Deaf Ears

Sadly this truth may never be revealed to English-speakers, except maybe via sketchy scanlations. For whatever reason, be it the retro art-style, poor marketing, or the public’s insatiable appetite for sub-par manga, only a fraction of Umezu’s rich catalog has been released outside of Asia.

I Am Shingo is too inaccessible, Fourteen, too long (and crazy). But if Ozaki Kyoko’s Helter Skelter can get licensed, then Baptism—the template for Ozaki’s tale of maternal terror, mental breakdowns made flesh, and cosmetic surgery gone wrong—could easily follow suit. And what gore hound isn’t licking their chops at the thought of God’s Left Hand, Devil’s Right Hand?

Araki hasn’t fared much better. Viz risked Jihad in publishing Stardust Crusaders, and the OVA based on the series has since gone out of print, ostensibly to appease the outcry from Islamic fundamentalists over the scene of Dio reading from the Quran. Perhaps this same fear of controversy is one of the factors keeping the excellent new JoJo anime off official streaming channels. Thankfully, NBM Publishing doesn’t negotiate with terrorists and has released the one-shot Rohan at the Louvre to fabulous reviews.

Rich Soundscapes

|

| "MEMETAH!" The noise your fist makes when striking a wet frog against a solid rock, obviously. |

Perhaps the problem is that much of the charm is lost in translation. In their Native Japanese, Araki’s turns of phrase are theatrical though succinct, as memorable as a good tag line. Umezu’s lexicon is smaller than the Esperanto dictionary, resulting in a cadence as recognizable and ripe for parody as Dr. Suess. A good wordsmith will be able to hammer the language into readable English, but some elements are unmalleable—namely, the sound effects.

|

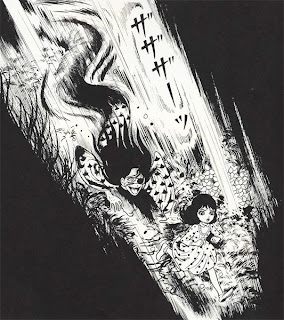

| Snake woman are one of the many things that go "ZA-ZA-ZA" in the night. |

This stylized graffiti is part of the art, an independent character that lives off the page. It’s the dramatic sting in a world without sound. GO-GO-GO-GO coils around JoJo like a viper ready to strike. Creepy-crawlies scuttle after helpless schoolchildren with a raspy ZA-ZA-ZA. These symbols are part of the author’s made-up language with tones more shrill than the exclamation mark, more booming than the period. Without them, the reader only hears half the story.

You Can't Spell "Fanatic" Without...

The sound effects are so iconic that JoJo fangirls have taken to painting them onto their tights with magic markers in lieu of the conventional leopard spots and star storms. Last July pro-otaku Shokotan appeared on the late-night celebrity variety show Ame Talk sporting Araki-spangled spats, which inspired a string of imitations on Twitter and manufactured knockoffs. You can't blame them for wanting to look their best for the then-trending JoJo Exhibition art show.

|

| Hardly an isolated case. (Source) |

|

| The Shibuya scramble brought to a standstill. THE WORLD! |

Fad fashion notwithstanding, JoJo devotees have always innovated ways to show their appreciation for the work in ways other than mindless consumption. Seichi junrei, the practice of touring real-world locals that appear in anime and manga, normally ends as an indulgent day trip. As with all things JoJo, the fans take this over the top. Members of the JoJo's Posing School, an online collective of contortionists with a flair for the dramatic, gathered to invade Sendai, the model for the fictional town of Moriocho from Part 4 to recreate famous scenes, hit up landmarks, and prostate themselves in worship at the station. And that's when they're not busy forming flash mobs a hundred strong in the middle of Tokyo's busiest intersection.

What Umezu's fans lack in organization they more than make up for clinically intense dedication. One took up entomophagy to recreate the cockroach force-feeding scene from Baptism. The gross-out factor is trumped by the creep-out factor of Kaneko Demerin, Umezu’s self-appointed “official stalker” and the only entity that keeps the master of the macabre up at night. A cult has gathered around the charismatic manga-ka, though it’s not clear if he has any control over it.

Doomsday Prophets

Umezu’s long-form serials read like time-shifted parables from humanity’s dystopian future. Drifting Classroom warned against climate change, I Am Shingo predicted aberrant AI in a pre-Internet age, and Fourteen explored the inevitable exodus of Earth aboard interstellar space arks, causing whispers that he was the next Nostradamus.

Araki also made an unwitting prediction—just one, though chilling in its precision. Part 3 of JoJo features the brothers, Oingo and Boingo (Zenyatta and Mondatta in the Viz translation), the latter of which commands a comic book-shaped Stand that predicts the future—anything printed on its pages comes true.

In this case, a traveler is fated to stab his neck on an electric pole and die at 10:30—an ominous time given the numbers 9-11 displayed on his T-shirt. If the the shark-toothed jumbo jet and Islamic crescent moon seem like just a coincidence, remember that the North Tower of the World Trade Center collapsed mere minutes before 10:30.

Even if Araki can auger future tragedies, especially those involving extremists, he is powerless in his predictions. Otherwise he wouldn’t have drawn mosques being blown up in the final showdown between Dio and Jotaro, or allowed Dio to read from the Quran in the OVA, both incidents that drew howls of outrage from fundamental Islamists and likely shut JoJo out of the western market. But the situation isn’t hopeless. Fate is not to be fought, but to be overcome, as Araki might say.

Phantom Blood

Anecdotal evidence shows that manga artists die young. Tezuka and Ishinomori both dropped out of the race at 60. Kamimura Kazuo passed away at 45, the prime of his life, and took Gekiga with him. The unrelenting deadlines and years spent hunchbacked over the drawing board take their toll.

Umezu has no right to still be kicking all things considered. He simultaneously juggled 3 weekly and 3 monthly serials at his peak. His abused wrists fell to carpal tunnel syndrome in the early ‘90’s during the publication of Fourteen, forcing him into an early retirement. But at 76 he’s more spry than entertainers half his age, leaping across the concert stage in leather chaps and showing his love for slapstick on year-end TV specials.

Still, time flows in one direction and erodes your body with age. Unless you happen to be a Hamon master like Araki. He looks more dapper at 50 than at 40, leading the public to speculate—perhaps the Stone Mask is more fact than fiction.

Cool Uncle, Hip Granddad

More likely, it’s the music that keeps them young. Rocking everything from Prince to Def Leppard to Lady Gaga, Araki is a professed album addict and DJs in his studio to match the mood of the current scene. Heavy metal for fights, folk ballads for lonesome treks through the wilderness. And always, always prog rock.

While not as vocal about his musical preferences, Umezu is closer to the artist themselves, penning lyrics for ani-song starlet Horie Mitsuko and Chikada Haruo, the J-pop taste-maker of his day. Umezu says that if he failed as a manga-ka he would have become a rockstar instead, a dream fulfilled by his studio cuts, Yami no Album I and Yami no Album II.

Araki is known for crafting fabulous outfits and flamboyant poses, something that came to the foreground in Part 3 to help personalize Jotaro's international traveling crew. A full wardrobe is mandatory for any series that wants to be taken seriously. But this wasn't always the case. Early characters dressed as drab as Charlie Brown until Umezu started importing designs from fashion magazines. Makoto-Chan, often laughed off as a dysfunctional family gag manga, is a lookbook stuffed with playful and pop designs. Except they're sandwiched between steaming turds, bodily fluids, and grandma's hanging tits.

Arivaderchi

While not as vocal about his musical preferences, Umezu is closer to the artist themselves, penning lyrics for ani-song starlet Horie Mitsuko and Chikada Haruo, the J-pop taste-maker of his day. Umezu says that if he failed as a manga-ka he would have become a rockstar instead, a dream fulfilled by his studio cuts, Yami no Album I and Yami no Album II.

Araki is known for crafting fabulous outfits and flamboyant poses, something that came to the foreground in Part 3 to help personalize Jotaro's international traveling crew. A full wardrobe is mandatory for any series that wants to be taken seriously. But this wasn't always the case. Early characters dressed as drab as Charlie Brown until Umezu started importing designs from fashion magazines. Makoto-Chan, often laughed off as a dysfunctional family gag manga, is a lookbook stuffed with playful and pop designs. Except they're sandwiched between steaming turds, bodily fluids, and grandma's hanging tits.

Arivaderchi

If you set these two up on a blind date, they’d have no shortage of things to talk about. Favorite bands, cinematic inspirations, Umezu’s love of Dali’s surrealism versus Araki’s respect for Michelangelo and the Mannerists. The former can’t draw anymore, the latter can only draw JoJo—how awesome would it be to see them collaborate on something fresh that plays up their strengths?

Super awesome, though impossible. Araki is absorbed with his art, Umezu is absorbed with his ego. This article may be the last time you see them both in the same place at the same time. Perhaps its for the better. Space-time would likely warp around the combined gravity of their careers, not to mention the potential risk of causing a grandfather paradox should they turn out to actually be dimensional-shifted versions of each other.

Inter-dimensional travelers or otherwise, Umezu and Araki hold a strange sway over the multi-verse of manga. An electromagnetic force invisible in the West, but tangible enough at their epicenter of the East Pole to make your hair stand on end. Unseen in their omnipresence, like a Stand or wandering spirit. And unknowable but hinted at by history, same as the fate of our civilization.

Inter-dimensional travelers or otherwise, Umezu and Araki hold a strange sway over the multi-verse of manga. An electromagnetic force invisible in the West, but tangible enough at their epicenter of the East Pole to make your hair stand on end. Unseen in their omnipresence, like a Stand or wandering spirit. And unknowable but hinted at by history, same as the fate of our civilization.

No comments:

Post a Comment